Strategy (Expansion of the SGEP)

Collected Resources for Scrum Guide Expansion Pack

This document is a collection of independent works. Each section retains its original license or copyright status, as indicated. Please refer to each section for specific usage rights and requirements.

top

Why Strategy Matters for Every Scrum Practitioner

If your Scrum Team runs smoothly yet fails to create real impact, you’re experiencing a common cause of Scrum adoption failure: the absence of clear strategic direction and effective strategy deployment. Many teams fall into “Zombie Scrum” - mechanically following practices without understanding the bigger picture, holding great events, and delivering working increments that struggle to create meaningful value. The missing ingredient is strategic thinking integrated with Scrum’s empirical approach, where decision-making is distributed, and propositions emerge from the people closest to the context and strategic challenges.

topStrategy Isn’t Just for Executives

When Scrum Teams are excluded from the strategy process, they lose the context needed to make value-driven decisions. Without understanding the “why” behind their work, teams optimize for output metrics like velocity rather than meaningful outcomes. This disconnection wastes their closest-to-the-work insights—the very perspectives that could reveal better approaches, identify emerging opportunities, and challenge assumptions. Strategic engagement transforms teams from task executors into intelligent contributors who can adapt their work to serve product or organizational goals, making real-time decisions that align with what truly matters.

Consider three Scrum Teams building e-commerce features. Team A focuses on burning down Story Points. Team B focuses on completing Product Backlog Items. Team C focuses on its strategy to “increase small business seller success rate from 12% to 40% within two years.” Team A plays velocity bingo, claiming outputs, even though they focus more on being busy. Team B delivers features but does not check if they effectively streamline operations. Team C, however, makes trade-offs between discovery and delivery, making decisions that are directly aligned with their strategic intent.

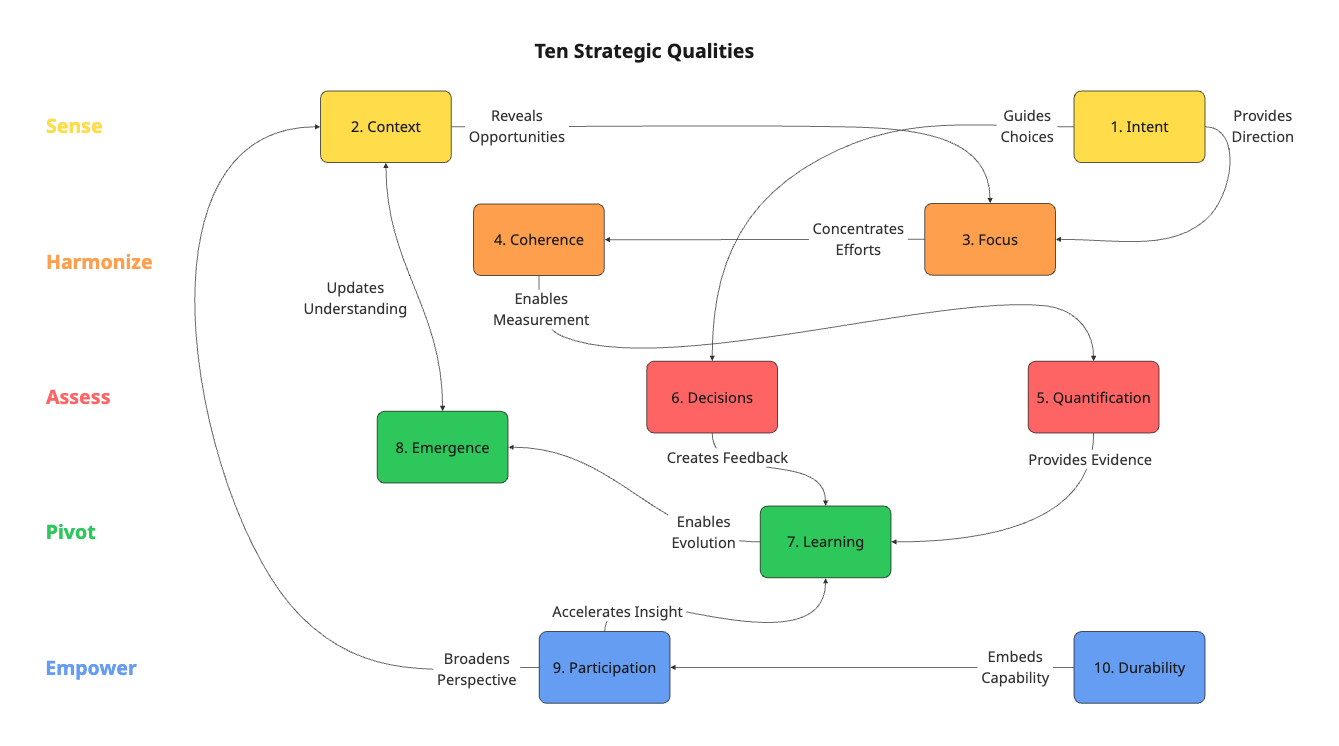

top10 Strategic Qualities You’ll Learn

This guide introduces ten strategic qualities (image below) that can transform good Scrum Teams into exceptional ones. It represents one curated perspective from selected influential leaders, rather than a definitive view resulting from exhaustive analysis. You’ll learn how to connect daily work to meaningful outcomes and business impact, make better decisions when priorities seem to conflict, contribute strategic insights from your unique perspective, and navigate uncertainty while maintaining focus.

Strategy isn’t about abandoning Scrum’s empirical nature - it’s about thinking more clearly about the value Scrum Teams create and why it matters.

top1. Intent - Providing Direction Without Dictating Solutions

Intent provides the animating purpose that energizes strategic action. Strategic intent answers “What future are we trying to create and why does it matter?” Unlike detailed plans that become obsolete when conditions change, intent provides stable direction while enabling tactical flexibility and responding to reality.

Consider these points regarding the intent behind a strategy:

- Clear intent enables distributed decisions through three key elements. They are Clarity (understanding strategic direction), Competence (the skills to contribute meaningfully), and Control (the authority to act on that understanding) [24]. When developers understand that “we’re building for enterprise reliability,” they choose technical approaches without approval, shifting from order-takers to strategic contributors. However, clarity alone can create frustration—teams must develop capabilities through training and coaching before they are granted decision-making authority.

- Intent provides a direction of travel, not fixed destinations. Specify the heading (toward customer autonomy or reduced complexity) while remaining open to discovering the path—in complex environments, the landscape changes as you move [11]. This closes Bungay’s “Knowledge Gap” by providing direction with less detail rather than more detail with less clarity. When teams understand “increase enterprise retention,” they seize opportunities (improved onboarding, better support) without waiting for prescriptive plans [5].

- Strategic intent describes an aspirational future that’s always capable of improvement, like a North Star that orients your journey rather than a destination to reach. Design your ideal as if starting from scratch, unconstrained by current limits [2], but recognize this “one level out of reach” reference point guides ongoing decisions rather than representing completion [8].

Now that we have covered intent, we also need to consider context, as strategic direction is meaningless without an understanding of the environment you must navigate.

top2. Context - Adapting Strategy to Specific Conditions

Context demands strategy adaptation to specific conditions; effective strategies should not be copied and pasted between organizations without also making adjustments for differences in context. Context includes, but is not limited to, market dynamics, organizational capabilities, work climates, cultures or sub-cultures, legal regulations, and competitive landscapes.

Consider these points regarding how contextual your strategy is:

- Strategies must be designed for specific circumstances, not copied from templates or “best practices.” Strategy begins with diagnosing the critical challenge or “Crux”—understanding the specific problem blocking progress and why [30]. A good diagnosis assesses the current reality and identifies what is preventing progress, creating a foundation for action. Without an accurate diagnosis of context-specific challenges, strategy becomes generic platitudes disconnected from real problems. Generic strategies fail because what works brilliantly in one context may be completely ineffective in another.

- Match your strategic approach to the nature of your challenge. Clear challenges require best practices; complicated ones require expert analysis; complex ones demand experimentation; and chaotic situations require immediate action [33]. Mismatched approaches to context fail—applying best practices to complex problems oversimplifies, while experimenting in clear domains wastes time and money. Organizations need balanced portfolios across challenge types, not single approaches, regardless of context. [34]

- Make context visible and shared through collaborative discovery. Use visual tools such as Wardley Mapping [37], Estuarine Mapping [10], or the X-Matrix [31] to create shared understanding—when teams see the same landscape, they align on reality rather than argue from different experiences and assumptions. Use workshops involving diverse voices or sense-making approaches to identify context-specific challenges and opportunities, surfacing insights from people closest to customers and operations that top-down analysis misses [33] [36].

Now that we have covered context, we also need to consider focus because understanding your environment reveals countless possibilities, but you cannot pursue them all.

top3. Focus - Concentrating Where You Can Win

Focus means making deliberate choices about where to compete and where not to compete, concentrating people, resources, and attention on areas of high leverage or potential advantage. Strategic focus is like a laser beam versus scattered light - concentrated energy creates breakthrough power while diffused effort barely illuminates nearby objects.

Consider these points regarding how focused your strategy is:

- Strategy is fundamentally about choosing what to focus on and what to ignore—deciding what not to do is as important as deciding what to do. Focus on the key addressable challenge (the “Crux”) that, if overcome, would unlock the greatest strategic progress [30]. Rather than scattering efforts across multiple issues, concentrate resources on the critical bottleneck or high-leverage problem. Every “yes” to one initiative is an implicit “no” to alternatives—without clear choices about what to ignore, everything becomes a priority, and nothing receives sufficient focus.

- Apply work-in-process limits at the strategy level—organizations can only execute a limited number of strategic initiatives effectively. Just as Scrum teams limit their Sprint scope toward the Sprint and Product Goals, organizations must limit their strategic portfolio size to what they actually have capacity for [21]. Too many strategic priorities dilute focus, create context-switching overhead, and prevent any initiative from receiving sufficient attention to succeed. Focus on proximate objectives—goals that are close enough to be feasible and actionable—rather than distant, aspirational targets, building strategic progress through achievable next steps within reach [29].

- Focus on where you have genuine sources of power. These could be distinctive capabilities, advantaged positions, or leverage that competitors cannot easily replicate [29]. Build a strategy around amplifying unique strengths (proprietary technology, network effects, specialized expertise) rather than competing where others are stronger. However, balance deep focus with peripheral awareness: create mechanisms for scanning weak signals, emerging threats, and unexpected opportunities through exploration time and diverse sensing networks. Too narrow a focus risks disruption; too broad an attention dilutes effectiveness.

Now that we have covered focus, we also need to consider coherence because concentrated efforts still fail when your chosen initiatives contradict each other.

top4. Coherence - Aligning All Elements for Maximum Impact

Coherence ensures that policies, actions, and resources work together toward unified goals rather than conflicting or canceling each other out. Like a symphony orchestra, where every instrument plays in harmony, strategic coherence requires all elements to reinforce one another rather than conflict. Coherence may create tension with focus, e.g., for a coherent outcome to be achieved, different Product Backlog Items need completion.

Consider these points regarding the coherence of a strategy:

- Strategic elements must reinforce each other like chain links—overall strength depends on integration, not individual excellence. “Where to Play” and “How to Win” form matched pairs: you can’t play in premium markets while winning through the lowest cost; they are integrative [15]. Each choice constrains subsequent choices: markets determine winning approaches, which determine capabilities, which shape management systems [25]. Coherence doesn’t require rigid perfection - just enough alignment to hang together without inner contradictions [7].

- Coherence extends beyond internal alignment to include coherent fit with the strategic landscape. A conventional strategy often fails by ignoring what others will do, like driving focused only on your destination while ignoring other traffic. However, ‘strategy is about changing your fit with the environment to your advantage by differential use of power and time.’ This means strategic elements must not only reinforce each other internally but also coherently address the external environment’s demands and opportunities**.** [18]

- Make coherence visible and testable through tools like the X-Matrix and Estuarine Mapping. The X-Matrix one-page format maps relationships between Aspirations, Strategies, Tactics, and Evidence [31]. Estuarine Mapping tells how your context can support your ambitions [10]. Ensure shared understanding through Backbriefing—ask teams to explain back their understanding of strategy and how their actions serve the larger purpose [5]. This surfaces gaps where teams recite strategy but haven’t internalized what it means for decisions.

Now that we have covered coherence, we also need to consider quantification because aligned elements require measurement to verify they create actual progress.

top5. Quantification - Making Progress Visible and Measurable

Quantification transforms strategy from wishful thinking into measurable progress. Instead of pursuing vague goals like “improve quality,” a quantified strategy specifies concrete targets such as “reduce critical customer incidents from 40-50 per month to fewer than 10 per month within 9-12 months.”

Consider these points regarding quantification of strategy:

- Abstract concepts become measurable through decomposition. Instead of measuring “customer satisfaction” directly, break it into components such as repeat purchase rates, referral frequency, or support ticket resolution time [19]. Tom Gilb’s Planguage provides a systematic approach: define the Scale (units like “minutes”), Meter (measurement methods like “survey”), and Target (specific goals like “reduce onboarding from 5-10 days to 2-4 days”). [16]

- Balance competing dimensions, don’t optimize single metrics. Troy Magennis emphasizes viewing metrics holistically across productivity, predictability, responsiveness, quality, sustainability, and value [22]. Goodhart’s Law warns that when a measure becomes a target, teams game it [17]. If lead time becomes a target, teams may cut corners to deliver more quickly, reducing quality as a consequence. Use metric trends as indicators for learning, rather than performance targets.

- Lead measures can enable action; lag measures validate desired outcomes in a direction. Lead measures track activities you control that predict success (such as “deployment frequency”), while lag measures track ultimate goals (such as “customer retention”) but can (depending on the duration of the lag) come too late to act on [26]. Connect measures to your diagnosed challenge - if users abandon during setup, measure “setup completion rate.” Ask “What challenge are we overcoming?” before “What should we measure?” [29]

Now that we have covered quantification, we also need to consider decisions because metric trends should guide the countless daily choices toward value throughout your organization.

top6. Decisions - Enabling Choices About What to Do and What Not to Do

Strategy serves as a decision enabler that helps people throughout the organization decide both what to do and what not to do. The power of strategy lies not just in defining direction, but in creating clear boundaries that help teams say “no” to activities that don’t serve strategic objectives. A strategy serves as a guide for countless daily decisions by providing clear criteria for evaluation.

Consider these points regarding how well your strategy enables decision-making

- Strategy emerges as a recognizable pattern from consistent decisions made over time. When a team consistently chooses to fix technical debt before adding new features, their actual strategy becomes ‘sustainable quality’—regardless of what’s written in any planning document [27]. More fundamentally, strategy is a deliberate commitment to concentrate time and energy in specific directions while explicitly eliminating other options. It’s saying “we will do THIS, and we won’t do THAT,” creating focused power to overcome challenges rather than spreading effort across every attractive opportunity [30].

- A good strategy acts like a compass for daily decisions throughout the organization, providing clear criteria that help people choose between competing priorities. Make explicit trade-offs and non-negotiables (what we’ll excel at versus what we won’t do) through interconnected decisions that reinforce each other: Where will we play? How will we win? What capabilities must we have? What management systems are needed? What must be true for this to work? [25]. This eliminates the need to debate every choice from first principles and prevents scattered priority lists.

- Make decisions clearer through quantification and context-appropriate approaches. Instead of debating whether something improves “quality,” measure, and reduce critical customer incidents from 45 per month to fewer than 10 within 12 months," giving everyone concrete evaluation criteria for pausing, pivoting, or persevering [16]. Match your decision approach to the situation using Cynefin: apply best practices in simple contexts, consult experts for complicated problems, run small experiments in complex situations where cause-and-effect is unclear, and act immediately in chaotic crises [33].

Now that we have covered decisions, we also need to consider learning, because consistent decision-making reveals patterns that show what works and what needs improvement.

top7. Learning - Building Capability Through Systematic Improvement

Learning represents the systematic capability to generate new information and knowledge for improved performance. Strategic learning builds the organization’s ability to generate insights, question assumptions, and create new knowledge through experimentation and experience.

Consider these points regarding how much learning a strategy supports:

- Distinguish between single-loop and double-loop learning. Single-loop asks “How can we fix this?” and adjusts actions while keeping assumptions unchanged. Double-loop asks “Why did this happen?” and “What beliefs led to this approach?” to question whether you’re solving the right problems [3]. Treat strategy as a testable proposition—when evidence contradicts your hypothesis, adapt based on learning rather than persisting with failed approaches.

- Run safe-to-fail experiments designed for learning, not just execution. Test strategic assumptions through experiments that are: small (failure won’t be catastrophic), quick (rapid learning), and parallel (exploring multiple possibilities simultaneously) [33]. Use nested PDSA cycles at multiple levels: Plan based on hypotheses or hunches, Do experiments, Study results, and Adjust by adopting, adapting, or abandoning based on evidence. Reframe failure as essential data that validates or invalidates assumptions and points toward better approaches [12].

- Create systematic capability for learning by distinguishing “red work” (doing the work) from “blue work” (improving how work gets done). Teams must allocate explicit time to step back from execution, learn from experience, and question whether they’re working on the right things in the right ways [23]. Build environments where people continually expand capacity to create desired results and nurture new patterns of thinking, not just react to problems [32].

Now that we have covered learning, we also need to consider emergence because systematic learning enables a strategy to adapt based on evidence rather than remain locked into obsolete plans.

top8. Emergence - Adapting Strategy Through Learning

Emergence enables strategy discovery through adaptation and experimentation by acting on new information and knowledge. While learning generates insights, emergence occurs when organizations respond to that learning. Emergent strategy develops like navigating uncharted waters with a compass - you maintain clear directional intent but adjust course based on discoveries as you go.

Consider these points regarding how strategy emerges from learning:

- Strategies may emerge as “patterns or consistencies realized despite, or in the absence of, intentions”. Successful strategies combine deliberate intent with emergent adaptation [27]. Organizations probe the environment through PDSA cycles and customer interactions, sense the patterns that emerge from results, and respond by amplifying successful approaches while dampening unsuccessful ones. This turns learning cycles into strategic evolution, where what actually works shapes direction more than what was originally planned.

- Emergent strategy works in the present by exploring adjacent possibilities rather than planning distant futures. Ask “What could we be right now?” instead of “What will we be in five years?” Identify what you can actually influence now, understand the energy and time required to shift it, and make small improvements that compound over time. This creates a strategy based on current reality and immediately actionable changes rather than future abstract plans [10]. As such, forecasting becomes sidecasting [35].

- Match your approach to context—emergence isn’t always necessary. In clear or complicated domains, use best practices and expert analysis. Emergent approaches are necessary for complex domains where cause-and-effect relationships are only clear in retrospect and require probe-sense-respond experimentation. Emergence is powerful in complexity but inefficient when proven solutions exist [33].

Now that we have covered emergence, we also need to consider participation because an adaptive strategy requires diverse perspectives that isolated leadership inevitably misses.

top9. Participation - Mobilizing Collective Intelligence for Strategic Success

Participation represents the active involvement of diverse voices in understanding, contributing to, and shaping strategy. Strategic participation recognizes that the best strategies emerge when people closest to the work, customers, and even other external stakeholders contribute their insights and expertise.

Consider these points regarding how people participate in strategy creation:

- Strategy is a creative design process undertaken by people who understand the specific context; It is not an analytical selection from predetermined options or external consultants’ menus [30]. Rather, it is generative, where new and original ideas are created by combining and transforming existing patters or information [15]. People closest to customers and operations have crucial insights that formal planning processes miss. Include diverse voices through collaborative workshops and participatory sense-making—when multiple perspectives contribute to understanding current reality and spotting patterns, emergent strategy becomes richer than top-down analysis could produce [6].

- Create a culture of psychological safety where people can contribute ideas, challenge assumptions, and admit mistakes without fear. When safety exists, teams engage in genuine dialogue—questioning strategies, surfacing problems early, and offering dissenting views that improve decisions [14]. Use structured processes like Ritual Dissent to make disagreement productive: create safe spaces where people can critique strategic ideas without defensiveness, surfacing blind spots, and strengthening proposals through collective intelligence. [9]

- Make strategy visible through tools like Obeya rooms and X-Matrix displays, where teams can see, question, and contribute to strategic thinking. When strategy is visibly present (whether physically or digitally) rather than hidden in documents, it invites dialogue—people can point to connections, identify gaps, and suggest improvements. Visibility democratizes strategy, moving it from leadership’s private domain into a shared space where anyone can participate in refinement [4] [31].

Now that we have covered participation, we also need to consider durability because broad engagement must embed strategic capability systematically so it survives individual leadership changes.

top10. Durability - Building a Strategy That Survives Leadership Changes

Durability means embedding the strategy and the strategy process so deeply into an organization’s operating system that they survive when leaders leave and don’t depend on inspired individuals. Strategic durability is about creating systematic strategy deployment and mobilization that enables anyone to lead strategic initiatives, rather than relying on charismatic leaders who become single points of failure.

Consider these points regarding how durable your strategy is:

- Build strategic capability across organizational levels rather than concentrating it in senior individuals. When strategy depends on specific leaders, their departure creates collapse. Develop systematic processes, shared frameworks, and distributed decision-making authority so strategic thinking becomes organizational competency, not personal heroism [24]. Create organizational capabilities for continuous adaptation through learning processes that endure beyond individual leaders—using retrospectives, pattern recognition, and documented learning—so strategic knowledge accumulates institutionally rather than residing only in key people’s heads.

- Embed strategic thinking into organizational operating models through systematic processes, measurements, and governance that make strategy execution routine rather than exceptional. Create regular cadences for strategic review, clear metrics for tracking progress, and decision-making frameworks connecting daily choices to strategic intent [20]. Use systematic frameworks that connect purpose to initiatives, initiatives to outcomes, outcomes to objectives, and objectives to tangible goals. When strategy deployment becomes part of how the organization operates—visualized through shared models and reinforced through regular PDSA cycles—it survives leadership changes because it’s woven into the organizational fabric. [31]

- Develop strategic capability through systematic coaching that teaches strategic thinking patterns—how to diagnose challenges, experiment with solutions, and learn from results. Rather than experts solving problems for teams, coaches build widespread competency, making improvement routine rather than relying on consultants or heroic leaders [28]. Develop future leaders systematically through coaching, mentoring, and involvement in strategy development, ensuring the organization’s strategy survives leadership transitions rather than starting over each time.

Your Strategic Journey Starts Now

topWhy This Matters to You as a Scrum Practitioner or Leader

If a Scrum Team runs smoothly yet fails to create real impact, the problem isn’t Scrum - it’s the absence of strategic clarity. When you understand the ten strategic qualities, you transform from a task executor into an intelligent contributor who makes value-driven decisions every Sprint.

When you understand the ten strategic qualities, you transform from a task executor into an intelligent contributor who connects daily work to meaningful outcomes, makes informed trade-offs, and navigates uncertainty with clear direction.

topStart Where You Are

Assess your situation and begin with qualities addressing your most pressing challenges:

- Unclear direction? Start with Intent and Focus via the Product Goal (toward the Product Vision)

- Features without value? Start with Quantification and Learning, and the separate Planguage and Value Planning booklet.

- Conflicting goals? Start with Coherence, Focus, and Decisions

- Disconnection from purpose? Start with Participation and Context

Remember: these aren’t isolated problems. They’re interconnected parts of what Russell Ackoff called a Mess, where “every problem interacts with other problems and is therefore part of a set of interrelated problems, a system of problems.” [1]. The ten qualities work together—improving one often improves others. The most important strategic capability of all is the ability to sense when things do not add up, and there is an invitation to rethink. The better you understand your part of the whole, the better you can do this.

topTake Action This Sprint

- All (esp. Leaders): What strategy does it look like we should be following?

- Scrum Teams: Add one strategic question to your next retrospective: “How did our last Sprint contribute to meaningful customer or business outcomes?”

- Product Owners: Explicitly connect your next Sprint Goal to broader strategic objectives. The Product Goal is what the Scrum Team is pursuing in the medium term, so test whether the Sprint Goal is iterating towards it. Make the “why” visible to your team.

- Developers: Before starting your next item, ask: “What customer problem does this solve, and why does it matter to our organization’s direction?”

Build Capability Over Time

- In the coming three months, implement one strategic practice. Visualize how your work connects to organizational direction or establish one leading measure of strategic progress.

- In the coming twelve months, develop systematic strategic capability. Build measurement systems tracking outcomes, not outputs. Create space for diverse voices in strategic thinking.

Strategy isn’t someone else’s job - it’s the foundation that makes all Scrum skills more effective. Every Sprint Planning session, every Product Backlog refinement, and every retrospective is an opportunity to think strategically about the value created.

The transformation begins now. Choose one quality. Take one action. Make the next Sprint count.

topReferences

| # | Reference |

|---|---|

| 1 | Russell L. Ackoff. “Redesigning the Future: A Systems Approach to Societal Problems”. John Wiley & Sons, 1974 |

| 2 | Ackoff, Russell L., Jason Magidson, and Herbert J. Addison. “Idealized Design: Creating an Organization’s Future”. Wharton School Publishing, 2006. |

| 3 | Argyris, Chris. “Teaching Smart People How to Learn”. Harvard Business Review, May-June 1991. https://hbr.org/1991/05/teaching-smart-people-how-to-learn |

| 4 | Benson, Jim and Tonianne DeMaria Barry. “The Collaboration Equation: Leadership and Collaboration in an Unpredictable World”. Modus Cooperandi Press, 2021. |

| 5 | Bungay, Stephen. “The Art of Action: How Leaders Close the Gaps between Plans, Actions, and Results”. John Murray Business 2010 |

| 6 | Burrows, Mike. “Agendashift: Outcome-Oriented Change and Continuous Transformation (2nd Edition)”. NewGenerationPublishing, 2022. |

| 7 | Burrows, Mike. “Wholehearted: Engaging with Complexity in the Deliberately Adaptive Organisation”. Agendashift Press 2025 |

| 8 | Cutler, John, Sean Ellis, and Amplitude Product Team. “The North Star Playbook: A Guide to Discovering Your Product’s North Star”. Amplitude Analytics, 2020. |

| 9 | Cynefin.Io. ‘“Ritual Dissent”. July 2023. https://cynefin.io/wiki/Ritual_dissent |

| 10 | Cynefin.Io. ‘Estuarine Framework’. March 2025. https://cynefin.io/wiki/Estuarine_framework . |

| 11 | Cynefin.Io. ‘Vector Theory of Change’. February 2023. https://cynefin.io/wiki/Vector_theory_of_change . |

| 12 | Deming, W. Edwards. “Out of the Crisis”. MIT Press, 1986 |

| 13 | Doerr, John. “Measure What Matters: The Simple Idea that Drives 10x Growth”. Penguin, 2018. |

| 14 | Edmondson, Amy C. “The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth”. Wiley, 2018. |

| 15 | Elvang, M. (2024) THE STRATEGY PLAYBOOK: Outcome-dependent corporate strategy in an UNPERFECT world: www.tinyurl.com/StrategyRetold |

| 16 | Gilb, Tom. “Competitive Engineering: A Handbook for Systems Engineering, Requirements Engineering, and Software Engineering Using Planguage”. Butterworth-Heinemann, 2005. |

| 17 | Goodhart, Charles. “Problems of Monetary Management: The UK Experience”. Papers in monetary economics 1975; 1; 1. - [Sydney]. - 1975, p. 1-20. Vol. 1. Sydney: Reserve Bank of Australia." |

| 18 | Hoverstadt, Patrick and Lucy Loh. “Patterns of Strategy”. Routledge, 2017. |

| 19 | Hubbard, Douglas W. “How to Measure Anything: Finding the Value of Intangibles in Business”. Wiley 2014 |

| 20 | Jackson, Thomas L. “Hoshin Kanri for the Lean Enterprise: Developing Competitive Capabilities and Managing Profit”. Productivity Press 2006 |

| 21 | Leopold, Klaus and Kaltenecker, Siegfried. “Flight Levels: Leading Organizations with Business Agility”. Flight Levels Academy, 2024 |

| 22 | Magennis, Troy. “Six Dimensions of Performance”. https://circle.flightlevels.io/c/blog/six-dimensions-of-performance |

| 23 | Marquet, L. David. “Leadership Is Language: The Hidden Power of What You Say - and What You Don’t”. Portfolio, 2020. |

| 24 | Marquet, L. David. “Turn the Ship Around!: A True Story of Turning Followers into Leaders”. Portfolio, 2013. |

| 25 | Martin, Roger L. Playing to Win: How Strategy Really Works. Harvard Business Review Press, 2013. |

| 26 | McChesney, Chris, Sean Covey, and Jim Huling. “The 4 Disciplines of Execution: Achieving Your Wildly Important Goals”. Free Press, 2012. |

| 27 | Mintzberg, Henry and James A. Waters. “Of Strategies, Deliberate and Emergent.” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 6, No. 3, July-September 1985 |

| 28 | Rother, Mike. “Toyota Kata: Managing People for Improvement, Adaptiveness and Superior Results”. McGraw-Hill 2009 |

| 29 | Rumelt, Richard P. “Good Strategy/Bad Strategy: The Difference and Why It Matters”. Crown Business, 2011. |

| 30 | Rumelt, Richard P. “The Crux: How Leaders Become Strategists”. PublicAffairs, 2022. |

| 31 | Scotland, Karl. “What is an X-Matrix?”. September 2017. https://availagility.co.uk/2017/09/04/what-is-an-x-matrix/ |

| 32 | Senge, Peter M. “The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of The Learning Organization”. Revised and Updated Edition, Currency, 2006. |

| 33 | Snowden, Dave, and Mary E. Boone. “A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making”. Harvard Business Review, November 2007. https://hbr.org/2007/11/a-leaders-framework-for-decision-making |

| 34 | Snowden, Dave. “Weaving risk and strategy …”. September 2025. https://thecynefin.co/weaving-risk-and-strategy |

| 35 | Snowden, Dave. “Sidecasting – a summary”. June 2024. https://thecynefin.co/sidecasting-a-summary/ |

| 36 | Stadler, Christian and Hautz, Julia and Matzler, Kurt and von den Eichen, Stephan F. “Open Strategy: Mastering Disruption from Outside the C-Suite”. MIT Press, 2021. |

| 37 | Wardley, Simon. “Wardley Maps: Topographical Intelligence in Business”. https://medium.com/wardleymaps |